“Two things form the bedrock of any open society- freedom of expression and rule of law. If you don’t have those things, you don’t have a free country,” wrote celebrated author Salman Rushdie. ‘The Satanic Verses’, Rushdie’s most controversial book partly inspired by the life of Prophet Muhammad that stirred a debate on various levels, was banned in India in 1988. Sure enough, not just the enlightened readers but the bureaucrats also knew a misdeed was being indulged on. 27 years later, in 2015, former finance minister P Chidambaram in a literary festival said, “I have no hesitation in saying that the ban was wrong”.

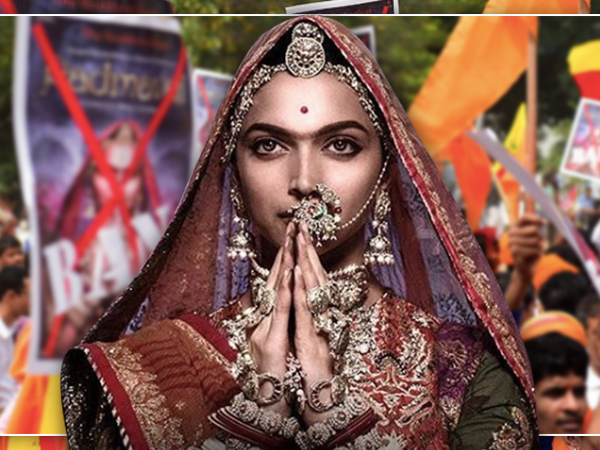

For the last few months, acts of protecting a mythical (will I be assassinated for using this term?) queen’s ‘dignity’ have occupied most of our social media mind-space. Demolition of sets, physical assaults on a veteran filmmaker, threats of beheading the actors, and a bounty on chopping off their body organs that originated from an overpowering sense of community prejudice, were to come to an end with the CBFC giving a green signal to release of ‘Padmaavat’. The Supreme Court, today, has lifted ban issued by six state Governments. But, is that worth a celebration?

The debate on cinematic liberty is a worn out one. How much imagination can be blended into how much fact, is best left to the artiste who fancies to tell his story. Agreed, in a country like India that boasts of vivid languages and folktales, we better not demean a particular identity or ideology, in the drive of being honest or expressive. Having said that, educating yourself to be open to opinions is a more progressive option than mastering the art of getting offended. And irrespective of which community you belong to, this applies to. In our sociopolitical structure, sadly, this is almost obsolete.

Precisely why, the mass response to ‘Padmaavat’ controversy is far more disappointing that a fringed group creating ruckus. Another acquiescence, that the inoperative state of openness and rationality lies far deep within.

A few days back, I woke to news of a group of Rajput women threatening to commit ‘Jauhar’ if the film releases. Whether it was a voluntary response to the situation or they were only being obligated by an organisation that claims to uphold their dignity, will remain a debate forever. In both cases, it raises the same question. Where are we heading to?

Going by statistics provided by the National Crime Records Bereau, a total number of 3,644 rape cases were filed in Rajasthan, in the year 2015, once reported Times of India. With this, Rajasthan acquired the third position in list of states with highest number of rape cases being reported. In the same state, a mythical queen’s dignity became so climacteric that the flag-bearers of dignity didn’t hesitate to issue threats on another woman. Sure enough, we are losing our minds. Hence, when women of the same state threaten to commit Jauhar (an act of sacrificing own lives rather than losing dignity to the opponent), whether willingly or reluctantly, because of a mere film, the menace is evident. Either the community bigotry is so deep-rooted that it takes over their own realisation of gender struggle; something they themselves have been fighting for decades now, knowingly or unknowingly! OR! The bigots are overpowering the sanes. Well, looks like they are! Either way, this is a huge, ironic blow; given that the queen in question is admired for putting her OWN honour against the evil.

Not long ago, I came across a social media post wherein the author accused Bhansali of portraying Peshwa Bajirao like a ‘Romeo’. “He instead of portraying Bajirao as a great warrior presented him as a weak Romeo,” he wrote. Hence, we should obviously NOT trust him with ‘Padmavati’, oops, ‘Padmaavat’.

‘Bajirao Mastani’ thoroughly glorified a warrior who not only showed great bravery at the war front, but fearlessly protected his own love interest till the moment he could. But more than that, to me, it was a more feminist film than many. It featured one Kashi Bai, a woman with a profound sense of dignity who never begged to be treated with more substance than Mastani, and Mastani herself, self-sufficient, beautiful and complementing her husband’s valour. If falling in love takes away Bajirao’s bravery for him, then I don’t know where are we heading with similar sort of wisdom.

Coming back to ‘Padmaavat’. The very fact that the self-proclaimed Rajput organisations blatantly refuse to even watch the film before they form an opinion, proves its baselessness and unencessity. In a few thousand years of civilisation, a few million communal conflicts gaze at us like enduring scars. We don’t need more of them.

To put it more simply, freedom of expression can’t be achieved by implementing a set of laws, until and unless we as citizens have assmmilated its cruciality.

Or should I say, The Satanic Verses of prejudice?

Journalist. Writer. Reader. Enthu cutlet. Mood-swing machine. Day dreamer. Sandwiched between ‘live life fully’ and ‘lose some weight’. Mantra of life: Love and love more.